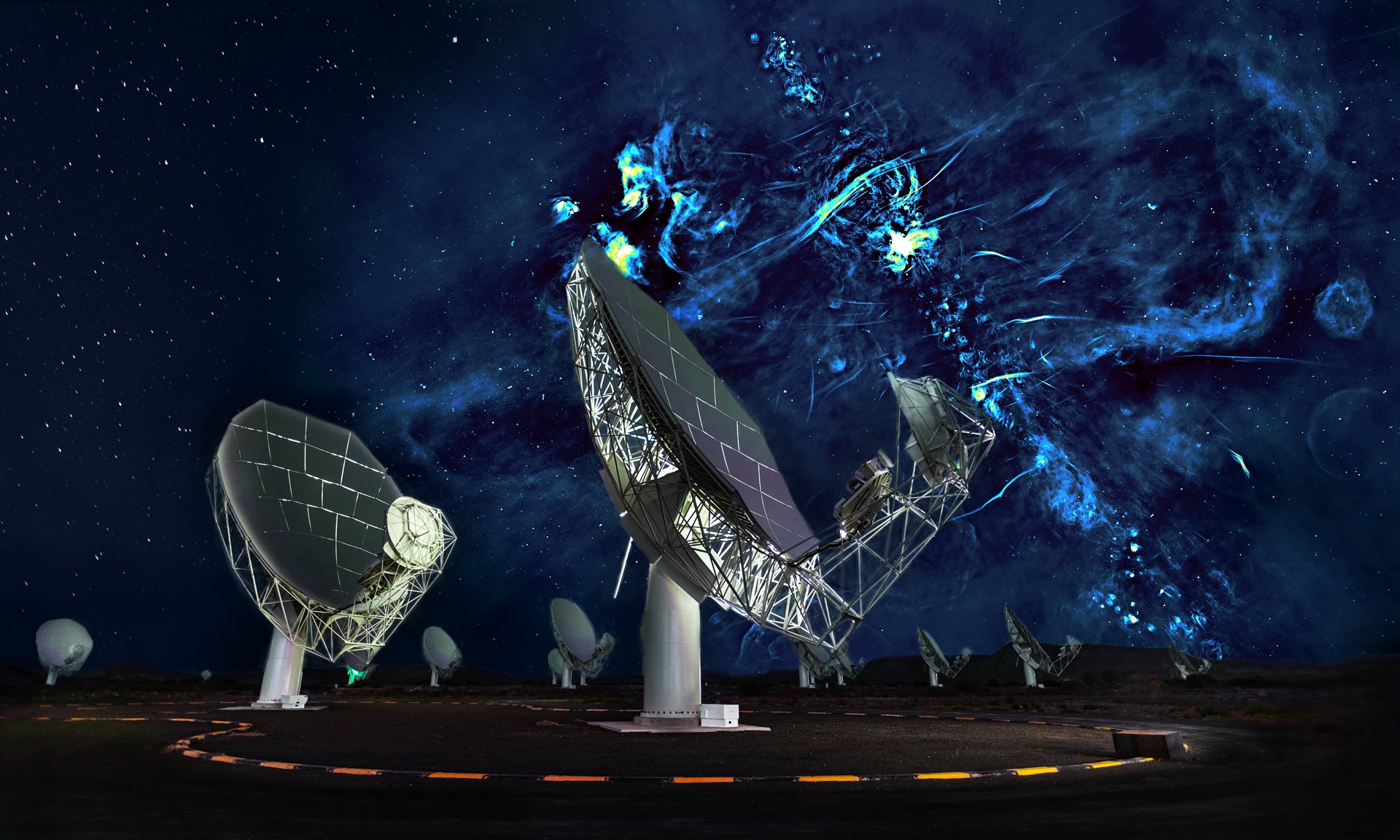

Last month, South Africa’s MeerKAT telescope discovered giant bubbles at the centre of our galaxy. This is the telescope’s second major finding—the first was one of the most magnetic objects in the Universe, a rare type of neutron star called a magnetar. But both of these discoveries were ‘accidents’, scientists say, and they are excited for what the telescope will find when it is really looking.

MeerKAT scientists observed the magnetar while the telescope was still being commissioned and not all of its 64 dishes were operational. The team then stumbled upon the giant bubbles at the centre of the Milky Way, thought to be the result of radiation exploding out of a black hole. The scientists had really been scouting for a “nice picture”, to show off the telescope at its inauguration in July last year, rather than planning to do any actual science.

“It is a really cool discovery,” South African Radio Astronomy Observatory chief scientist Fernando Camilo says of the radiation bubbles. But, he adds: “It wasn’t predicted and not what MeerKAT was designed to do.”

So what might MeerKAT discover next? The telescope was designed with specific scientific mysteries in mind. Many of these involve hydrogen—the lightest element on the periodic table and the most abundant in the Universe. Hydrogen is the fuel of stars, and astronomers can follow the traces of ancient hydrogen to get an idea of what the early Universe looked like.

“A lot of our science is the study of hydrogen throughout the history of the universe,” Camilo explains. Through the hydrogen-emission line, which is the signal astronomers look for to detect the element, scientists will be able to investigate how galaxies are formed and how they evolve, he says.

The science team had fun naming MeerKAT’s observing projects, and many reflect the telescope’s African heritage. One project that will trace ancient hydrogen is called Looking at the Distant Universe with the MeerKAT Array or ‘Laduma’.

Laduma is an isiZulu world meaning “it thunders”, and is shouted in South Africa when a football player scores a goal. The Laduma survey’s shape (through time and space) also resembles a vuvuzela, the plastic horn which is a common sight and sound at South African football matches. Ancient hydrogen spotted by Laduma will help piece together the puzzle of what the Universe was like just after the Big Bang, and understand how it is expanding.

Some of MeerKAT’s projects will be pilots for the giant Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which, when built, will form the largest radio telescope in the world with dishes and antennas scattered across Africa and Australia. One of these projects is the evocatively named Mightee (or the MeerKAT International GHz Tiered Extragalactic Exploration) project, which will look deep into space beyond the Milky Way to explore the evolution of galaxies. Mightee will act as a pilot for the cosmology experiments that the substantially more powerful SKA will undertake. Many questions remain about how galaxies form and evolve, and those answers could point to what happened when the first galaxies came into existence.

“Generally the MeerKAT science is strongly in line with the general SKA science drivers,” explains Patrick Woudt, head of astronomy at the University of Cape Town. Woudt leads the ThunderKAT large survey project, or ‘The HUNt for Dynamic and Explosive Radio transients with meerKAT’.

Astronomers and astrophysicists have become increasingly interested in transients. These are (usually) short-lived phenomena such as supernovae, gamma-ray bursts and fast radio bursts that can be easy to miss and restudy. Transients are some of the most mysterious and exciting phenomena in the Universe; this area of astronomy is growing quickly as astronomers try to figure out how to capture and understand these events before they pass.

ThunderKAT will use all the data gathered from many MeerKAT projects, and will be able to construct images of the radio sky on different time scales—from minutes to years, says Woudt. “This is a new way to maximising the potential discovery of new and unusual transient phenomena.”

MeerKAT will help astronomers make huge advances compared to older telescopes observing the same frequencies, says Woudt. This is due to its increased sensitivity, wide field of view (so they can sample more of the sky at faster time scales), clearer images, and finally because of its data policy, which will allow astronomers to search all the data for new and unusual phenomena.

It’s likely that the telescope will keep throwing up surprises for the scientists who operate it. Camilo, who came to South Africa from the United States specifically to work with MeerKAT, wonders what in 10 years the telescope will have helped discover. “Usually the most amazing things that are discovered are things we hadn’t considered,” he says.

Image credit: SKA