Tunisia has increased its investment in education and science, but many professionals leave the country, representing a loss on that investment. Now, a global network of young Tunisian scientists is feeding diaspora expertise back into the country.

Since gaining independence from France in 1956, Tunisia has made a lot of investments in education and science. In 2018 only two continental grantmakers—South Africa’s National Research Foundation and Tunisia’s Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research—appeared in the Top 10 of research funders in Africa. Also, last year Tunisia ranked 14th globally in terms of scientific output as a proportion of GDP.

A great deal of the investment has been in the life sciences, which include biology, medicine and biochemistry. A July 2019 search for ‘Tunisia’ in the online journal PubMed returned more than 21,000 articles, compared with only 13,500 for Morocco and 7,000 for Algeria.

However, many Tunisian academics live abroad. In 2015, the Tunisian diaspora represented approximately 13% of the Tunisian population. More than 100,000 researchers, doctors, and pharmacists are estimated to have crossed the sea and established themselves in Europe, North America, or the Arabic peninsula region, making brain drain a real concern.

For a young scientist growing up in Tunisia, this can be discouraging. But a young group of life scientists—of which I’m one of the founders—is working to change that.

It all started in December 2014 at a biology conference in Tunisia. A small group of us—some working in Europe, some in Tunisia—began to talk about how boring life science conferences were in our homeland. There would be the same old names as speakers, same old studies. There was no chance for young scientists to take up space and shake things up.

In our group, we had all graduated from Tunisian universities and spent at least one postdoctoral post outside Tunisia. We recognised the considerable role that the Tunisian science diaspora could play in the development of Tunisia in general, and science and education in particular. And so we set ourselves a crazy task: To organise a scientific event in Tunisia for young scientists within the next 12 months which we would call the International Symposium of Young Researchers in Biology in Tunisia.

To make sure our symposium was different to the others, we agreed on some fixed rules. Only (excellent) young researchers would be allowed as speakers. We invited both Tunisians and non-Tunisians. Those working abroad had to be principal investigators, but because it was not possible at that time to be a young PI in Tunisia, local speakers did not have to lead research teams in order to speak.

We also agreed that English would be the main language of our symposium. This was a first for Tunisia, where French is the language of science and where meetings are generally held in French. However, we felt that this tradition limited international participation.

I have to confess that it was not a popular decision at first. People thought it would be an obstacle to local participation, hinder audience-speaker interaction, and limit our success with sponsors. But others were enthusiastic, and in the end we just ignored the naysayers. We found that most young researchers were happy to speak English, which was comforting.

In the end, the speaker list included scientists from France, Italy, Singapore, Brazil, and Tunisia. Among the 180 participants were representatives from Algeria, Morocco, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, the United Arab Emirates, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore, and the United States of America. It was the first and biggest scientific event in the country to be 100% dedicated to young scientists.

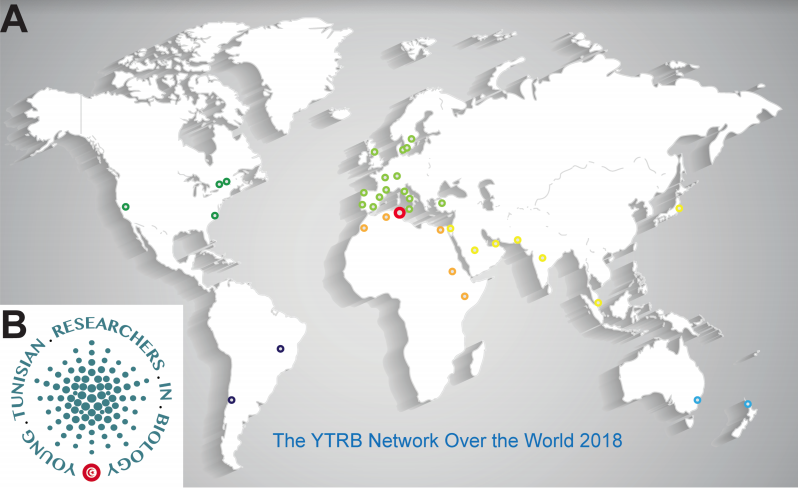

The symposium was a success, and we resolved to keep building on it. The Young Tunisian Researchers in Biology—or YTRB—network was born. It aims to connect young Tunisian scientists to peers all over the world, in order to share knowledge, experience, and technology. The network arranges the international symposium every second year in Tunisia. More than 100 participants took part in the second symposium, held in May 2018 in Hammamet. The next symposium will be in Sfax in March 2020.

The network also organises workshops to introduce new research techniques and skills to students in Tunisia and neighbouring countries. The workshops have covered protein modelling and docking (2016 and 2018), flow cytometry (2018), how to plan and get a postdoc (2018), and ‘from genomics to proteomics’ (2019). We will hold a workshop on using the fruit fly as a model for biomedicine in October this year in partnership with the DrosAfrica network and Sfax University.

In addition, we arrange videoconferences, inviting young scientists to give talks over Skype followed by a round of questions. The audience is located in a university auditorium with a local YTRB collaborator chairing it. We have organised video conferences at universities in Bizerte, Monastir and Sfax with speakers from Canada, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the USA. We also arrange smaller meetings, which are similar to the large symposium but focus on one subject—a technique, usually, or a scientific novelty. We have had one on laboratory animal science, which focused on introducing new and low-cost animal models to Tunisian laboratories.

We also train young Tunisian biologists to communicate their science to the wider public. In 2018, we launched communications awards for young scientists, with local journalists and members of literature associations forming a non-scientific judging panel. The awards will be given out annually.

In parallel with these scientific activities, YTRB has started a science diplomacy lobby group to promote Tunisian research outputs to the rest of the world. We have also started to offer our help to Tunisian public institutions as external experts. For example, when more than 15 babies died from infection at a hospital in Tunis, provoking public outrage, our network launched a project to study the infectious agents that caused the deaths using novel techniques, and to communicate the results to the public.

However, there have been obstacles in our path, the greatest being our limited resources. When we started our activities, fellow co-founder Chameseddine Kifagi and I contributed about €10,000 to get the project off the ground. To fund our conference, we have counted on several cultural exchange organisations in Tunis run by France, Italy, Germany, and Spain. We also obtained financial help from the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

The network is growing rapidly—we have hundreds of members all over the world. We still work on our visibility, and encourage young scientists to join us. But we have also faced silent—and sometimes not so silent—disapproval from some older heads of laboratories. It’s because of what we represent: young and diaspora scientists.

We believe that YTRB is bringing in a new age for Tunisian science. This is evidenced by the increase in meetings, symposia, workshops, and even research positions in universities with the tag “young scientist” attached to them. This definitely encourages us to continue our work and investment in the future of Tunisian science with the motto: Be Young, be Brilliant, be YTRB!

Visit our website (https://ytrbiology.weebly.com/) or Facebook page (Young Tunisian Researchers in Biology) and support the network. You can also contact us via biology.tun@gmail.com

Mohamed Jemaà is an expert in the field of genomic instability. Since 2017, he has been based at Lund University in Sweden. He dedicates this article to the memory of YTRB co-founder Myriam Fezai, who passed away earlier this year.