Cooler” cigarettes could reduce the damage to smokers’ lungs, according to new research published in Scientific African this month. Tobacco consumption kills up to 7 million people annually, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Although smoking affects every organ in the body, it has been conclusively linked to lung cancer. The United States’ Center for Disease Control reports that smoking is responsible for nine out of 10 lung cancer deaths. But the demographics of smoking are changing. About 80% of the world’s 1.1-billion smokers now live in low- and middle-income countries, says the WHO. Part of cigarettes’ deadliness is linked to the temperature at which they burn, the authors write in their paper, “Environmental inhalants from tobacco burning: Tar and particulate emissions.” “Most of the highly toxic pollutants usually evolve between 200 and 600 degrees Celsius,” says Joshua Kibet, study co-author and a chemist at Egerton University in Kenya.

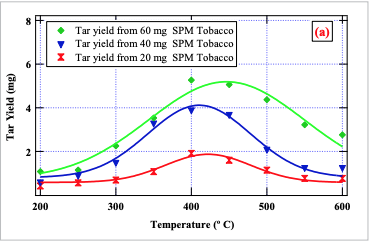

Their study aimed to determine which toxins and particles form at which temperatures and how these would attach to the lungs of a smoker. Previous studies have found that tobacco smoke contains more than 5,600 compounds in its vapour and particle phase. “The temperature at which maximum tar yields are produced is critical in designing cigarettes that can be smoked at lower temperatures and thus minimise the inhalation of harmful tobacco compounds,” the authors, from Egerton University and the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, write. To do that, the researchers mimicked a human lung, using a silica gel.

This gel absorbed the tobacco smoke particles, which the researchers then analysed using an electron microscope to determine their size. For legal reasons, Kibet says that they cannot disclose the brands of the cigarettes tested for the study, but he acknowledges that they were produced by major international tobacco companies. Ultimately, the study found that cigarettes produced high yields of tar between 300 and 400 degrees Celsius, and that designing cigarettes that burn at lower temperatures could reduce the damage to smokers’ lungs. It also found that the particulates in cigarette smoke are ultrafine, meaning that they can cause more damage to the lungs. Scientists and governments usually measure air pollution, such as pollution from cars and factories or even dust, in particulate-matter size. For example, PM2.5 and PM10 mean that the particles of pollution are 2.5-micrometres (μm) or 10μm in diameter. For comparison, a human hair is about 70μm wide. “Particulates from this study, and indeed most tobacco studies, are classified as PM0.1,” says Kibet. “Particulates from tobacco smoke are very small, and may be inhaled deeper into a person’s lungs causing serious biological harm.”

Interestingly, smokers who smoke quickly are at greater risk of inhaling these ultrafine particles. The researchers found that the cigarettes of those who smoke quickly burn hotter than those who smoke slowly (time and a lower temperature allow these ultrafine particles to congeal into larger ones). Kiset hopes that his research will enable cigarette companies to produce less harmful cigarettes. However, Paul Garwood, a communications officer at the World Health Organization, is sceptical. “Cigarettes are the deadliest consumer products on the market, which when used as intended have debilitating health outcomes,” he says.

“Several attempts have been made over the years to alter the characteristics of cigarettes, including light and mild cigarettes, and the inclusion of filter ventilation, with claims of reduced harm attributable to these modifications. However, science has proven that these modifications do not reduce the harmfulness of these products, as the resulting emissions from these cigarettes are just as harmful. Reducing the size of the tar particles will not reduce the toxic chemicals to which the smoker is exposed,” he says. The next step in Kiset’s research is to characterise the status of cigarette smoking in Kenya, and its link to socioeconomic variables such as education level and tobacco company marketing. “The results of [such a] study should be used to educate people on tobacco cessation strategies and minimise the economic burden caused by tobacco-related diseases such as cancer, oxidative stress, respiratory problems, and [premature] ageing.”