In 2015, 27-year old Kenyan Shabaya Beche and his friends were wondering how to dispose of some old electronic equipment. Between them, they had old computers, video games, cell phones, even a refrigerator.

“None of us had a better idea, then, besides throwing them into the bin,” says Beche, who at the time was a fourth-year Information and Communications Technology student at Africa Nazarene University in Nairobi, Kenya. But they had also heard about the economic potential locked up in electronic waste, or e-waste. So, rather than head to the dump, they brainstormed solutions.

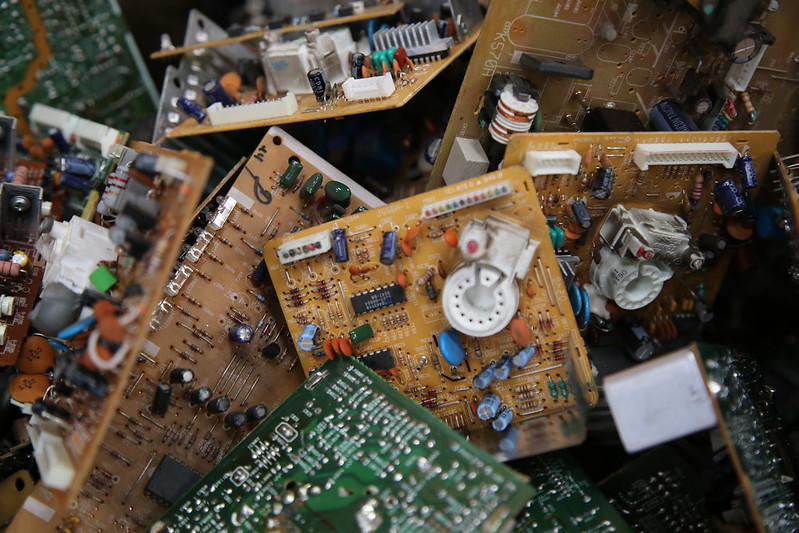

E-waste is one of the fastest-growing waste streams globally, predicted to reach 52.2 million tonnes in 2021. Often, it contains hazardous materials, like cancer-causing cadmium, which end up on landfills and can contaminate soil and groundwater. Compared with other continents, Africa generates little: a mere 2.2 million tonnes, or 1.9 kg per person, in 2016. But less than 0.2% of Africa’s e-waste is collected and recycled—a lost revenue stream, as the material value of e-waste alone is estimated at more than US$60 billion a year.

For Africa’s youth, it’s an opportunity to find work. Around 20% of Kenyans aged 15-24 years old were unemployed last year, according to official data. E-Waste could be a way for them to make a living.

Beche and his friends approached two faculty members at their university—Kendi Muchungi and Mark Mutinda—for help on how to turn their rubbish into something useful. Mutinda, who heads up environmental resource management at the university, taught them for free about the polluting aspects of e-waste. Muchungi, a computational neuroscientist, introduced them to design thinking as a way to identify problems in their communities that e-waste could solve.

The students registered a company, Squadra One, with the ambition of turning it into a training initiative for young Kenyans. In 2018 the company, the university, and Kenya’s environmental ministry arranged their first joint e-waste week, featuring a design contest for high-school girls.

The company—initially funded out of its founders’ pockets—has trained more than 200 university and high-school students. Its founders, who are now graduates, all return to volunteer as trainers. However the programme is no longer free—students pay KSh1,000 (US$10) each to participate. This buys them three training sessions, and they receive a certificate at the end.

One recent trainee, Timothy Marube, says the programme is a catalyst for innovation. It teaches students to conceptualise ideas, make a prototype, and then test and market it. “Now, I can transform an idea into a business,” he says. Marube, who participated in the training in 2018, repurposed an old portable rechargeable LED lamp into a street light that turns on when people move in its vicinity, as opposed to being on 24 hours a day. He wanted to solve the problem of insufficient energy in his community. “It is in the testing phase where I am refining it before it’s ready to enter the market,” he says.

Another alumnus from the training course—Martin Njuguna, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology in Juja, Kenya—used e-waste to build an automated greenhouse that monitors temperature, soil acidity, and moisture levels inside.

Njuguna has also managed to commercialise the knowledge he acquired by teaching others. He earns between KSh1,000-2,000 per one-hour session, and up to KSh100,000 for long-term projects. The income finances his startup company, which specialises in home automation and access control, and pays for his upkeep—food, rent, and tuition.

Training initiatives such as those pioneered by Beche and his friends are welcome, as it helps Kenyan youth become entrepreneurs, says Boniface Ngari, director for long-distance and e-learning at Multimedia University of Kenya. He says universities struggle to teach students such technical skills because they lack funding, and calls for sustainable solutions to address this bottleneck.

Image credit: Rwanda Green Fund/Flickr