In Nigeria,

She speaks to Linda Nordling about her work using oil consuming microbes found in nature to clean up such polluted sites, while at the same time improving the lives of the people who live there.

Nigeria is one of Africa’s largest oil producers. In October this year, the country’s wells were producing about 1.8 million barrels of crude oil every day. This wealth comes at a high environmental price, however. Many oil wells are located in ecologically delicate wetlands, and transported via pipelines to industrial refining sites. But decades of spills from routine exploration, accidents, sabotage or illegal artisanal refining, where locals break open pipelines to siphon off crude oil to refine and sell on have devastated local plant- and wildlife, and made people ill in nearby communities. But the wastelands caused by the oil industry may harbour the key to their own salvation: oil-consuming microbes that could restore the soils to their former glory.

Chikere, who has spent over a decade hunting these microbes, talks about her latest insights published in this issue of Scientific African and her plans for bringing oiled soils back to life.

How did you become interested in this field?

I did my MSc in industrial microbiology at the Federal University of Technology in Owerri, in Nigeria. My supervisor, Jude Ogbulie, was a consultant for some of the oil companies in the country. One day he observed something strange near an abandoned oil well: an algal bloom in the middle of all that pollution. That brought about my research project, which established that algae could live in and even digest the oil. I realised that if we can find ways of restoring the environment using those natural biochemical reactions, it could be a game-changer. That sparked my passion.

What is your Scientific African paper about?

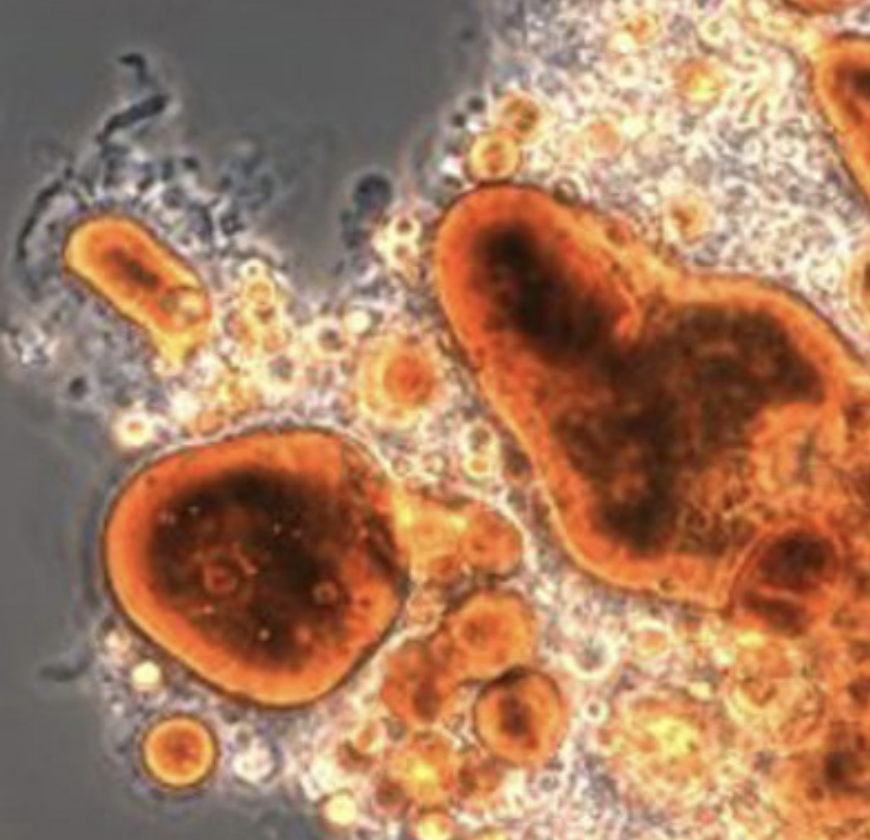

My co-author Emmanuel Fenibo and I collected soil samples from two sites that had been used for illegal oil refining. One was an island on the Sombrero river, the other a site close to the Bodo-Bonny bridge. These sites, both in Rivers State in southern Nigeria, were so degraded that the soil was calcified. There was no plant life, no greenery. The places were stripped bare to the eye, but we still found microorganisms in the soil. These microorganisms are able to use hydrocarbons as sources of energy. We took the samples to the lab where we studied their hydrocarbon concentrations, especially polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which pose high risk to human health. In fact, they can cause cancer. We then isolated bacteria from the samples that were able to feed on PAHs, extracted their DNA, and studied it. We found that bacteria from both sites contained nahAc and PAH-RHDa-GP, two genes which express proteins that are able to digest hydrocarbons. That showed the bacteria were most likely helping to degrade the dangerous hydrocarbons in these soils.

Was it difficult to get access to the sample sites?

It was very hard! The local communities are distrustful of strangers. They do not see the benefits from the oil industry, and sometimes they break open pipelines and siphon off oil to crudely refine and sell. It’s a messy business. Luckily, my co-author, who was my MSc student at the time, hails from one of the communities. He was able to negotiate access. We explained to the communities that we believed the research would benefit them; not just by restoring their land, but also by generating income. We paid locals to use their boats to access the field sites. We now have another ongoing project to try to rehabilitate calcified soils. That project is creating even more employment.

How are you restoring the soil?

The bacteria we found are aerobic, which means they need oxygen to break down the dangerous hydrocarbons. We are trying to see whether we can speed up the process in the soil by tilling it to get more oxygen into it. We employ local youth to till the soil. Then we add manure as a fertilizer, which we buy from locals as well, and we pay locals to transport it.

What are the results so far?

A little over three months after starting the rehabilitation process, known as bioremediation, the sites have been transformed. A place that was stripped bare of vegetation now has full vegetation. Gradually, the soil is bouncing back. It’s a very simple and affordable way of treating the soil, that the locals can do themselves. This was important any technology we developed had to be applicable in the local context.

How healthy is the soil afterwards? Can you use it to grow food?

That’s the next thing we want to look at. At the moment what’s growing at these sites is wild weeds and shrubs. The next stage will be to look at the plants;, are they concentrating the chemicals in their parts? As we speak my co-author, who is now my PhD student, is working on this.

We also want to look closer at the bacteria we have found to see if we can identify among them especially voracious consumers of hydrocarbons that may have evolved in these soils. We’d like to do high-throughput and whole genome sequencing of these microbes so we can isolate the enzymes and genes that allow them to break down oil so efficiently. Unfortunately, in Nigeria, we are limited by a lack of equipment and facilities. At the moment, we have to do some of our advanced laboratory analyses in South Africa. We hope that in future, we will be able to apply for grants and get funding that can help us address this lack of equipment at home.